Sidetrack Post: Some Notes on Method

Making my method more explicit, and answering the question of "why?"; or, The Not-Sidetracked Post: The Nicene Creed as the Standard of the church, among other things.

[Note: I am stealing part of the way that I title this post from Stephen Guerra of The History of the Papacy Podcast. Steve often has “Sidetrack Episodes” that dive into different aspects of Christian history that don’t fully fit within the narrative that he is telling, but are important pieces of context for fully understanding the story of church history as a whole. If you haven’t checked out The History of the Papacy Podcast, I encourage you to do so!

As a few of you have noticed, I’ve been a bit slow to publish my latest piece on Liturgy as Sacred Tradition. It is not because I’ve not worked on it. In fact, I’ve added to it and/or re-edited it at least five times now. But, as with teaching or staking a claim in an argument, I find that writing often reveals the holes in my own knowledge. So, as I write, back to research I go, reading up on ideas, reading various primary sources, reading what liturgists of various churches have to say about the liturgy and its purpose, etc. So, I am continuing to work on that post in my series, but owe you another.

Over the past few weeks, I’ve read not a few Episcopalians and Anglicans on social media lament the lack of any type of uniform theology within Anglicanism. This is not a new lament/criticism within the communion or from without. John Henry Newman, who was a Priest in the Church of England and also a leader in the Oxford Movement, was tormented by this fact, and complained of it in his speeches and writings. Not to over simplify things, but a lack of defined doctrine was absolutely one issue that compelled Newman to swim the Tiber for Rome. And, that is not an unfrequently heard plan in many places where Anglicans tend to gather online. While I am sympathetic to those complaints, I do believe that Anglo-Catholicism can and should in fact work towards a more defined theology.

Saying that out loud, however, can almost be a way to start a brawl in this communion. One thing that many Anglicans like (myself included) is that the church (at least, in my context, The Episcopal Church) has few established dogma’s, and defines the faith in a way that affirms the core beliefs of historic, apostolic Christianity, while leaving the majority of believe and practice up to individual parishes, rectors, and individual Christians. This lack of definition is both a blessing and a curse. On the side of blessing: it allows me to do exactly what I am doing now, which is making a contribution to the communion of some thoughts about how properly theology ought to be done in Anglo-Catholicism. On the curse side, because the church have granted a larger level of freedom to belief and practice than most other Christian churches, two things seem to occur: first, often LITTLE to NOTHING is taught one way or the other in the context of Christian formation, education, and homiletics, and, some take freedom as license to practice of allow anything.

Both of these “curses” are a serious problem, however, the second one is more of a problem that needs to be handled first, and the second a bit later (both logically and strategically). In the past several months, I’ve seen a decent number of folks come onto the Episcopalian Subreddit asking similar questions, which I will distill down to the following: “I am a practicing pagan [or witch]. I don’t believe in the Creed. I need some place where I can have community. I have heard I might be welcome here. Can I still be a member of your church even though I don’t believe in God?”

Now, don’t get me wrong: I am ABSOLUTELY NOT saying that we should not welcome people into our worship and community with open arms. In fact, we absolutely should make space amongst ourselves for those not like ourselves, because there is in fact a reason that these people are being drawn to our assemblies. To say no to these folks would be to deny a crucial place to evangelizing those who walk into our door seeking something more.

What I am saying is that our answer to this question must be well-thought out and nuanced. Everyone is welcome at the Episcopal Church. However, while everyone is welcome, not everyone is eligible to become a member. The canons of The Episcopal Church are quite clear here. Title I, Canon 17, Section 1, says:

a. All persons who have received the Sacrament of Holy Baptism with water in the Name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit, whether in this Church or in another Christian Church, and whose Baptisms have been duly recorded in this Church, are members thereof.

b. Members sixteen years of age and over are to be considered adult members.

c. It is expected that all adult members of this Church, after appropriate instruction, will have made a mature public affirmation of their faith and commitment to the responsibilities of their Baptism and will have been confirmed or received by the laying on of hands by a Bishop of this Church or by a Bishop of a Church in full communion with this Church. Those who have previously made a mature public commitment in another Church may be received by the laying on of hands by a Bishop of this Church, rather than confirmed.

So, while anyone is welcome, not everyone is called to be a member. And, to become a member of the One, Holy, Catholic, Apostolic Church, a valid baptism is and always has been the requirement of entrance. This is an area that must not be compromised. It is, of course, a part of Nicene Creed, which states:

We believe in one holy catholic and apostolic Church.

We acknowledge one baptism for the forgiveness of sins.

We look for the resurrection of the dead,

and the life of the world to come. Amen.

The creed also has another dogmatic requirement:

We look for the resurrection of the dead, and the life of the world to come. Amen.

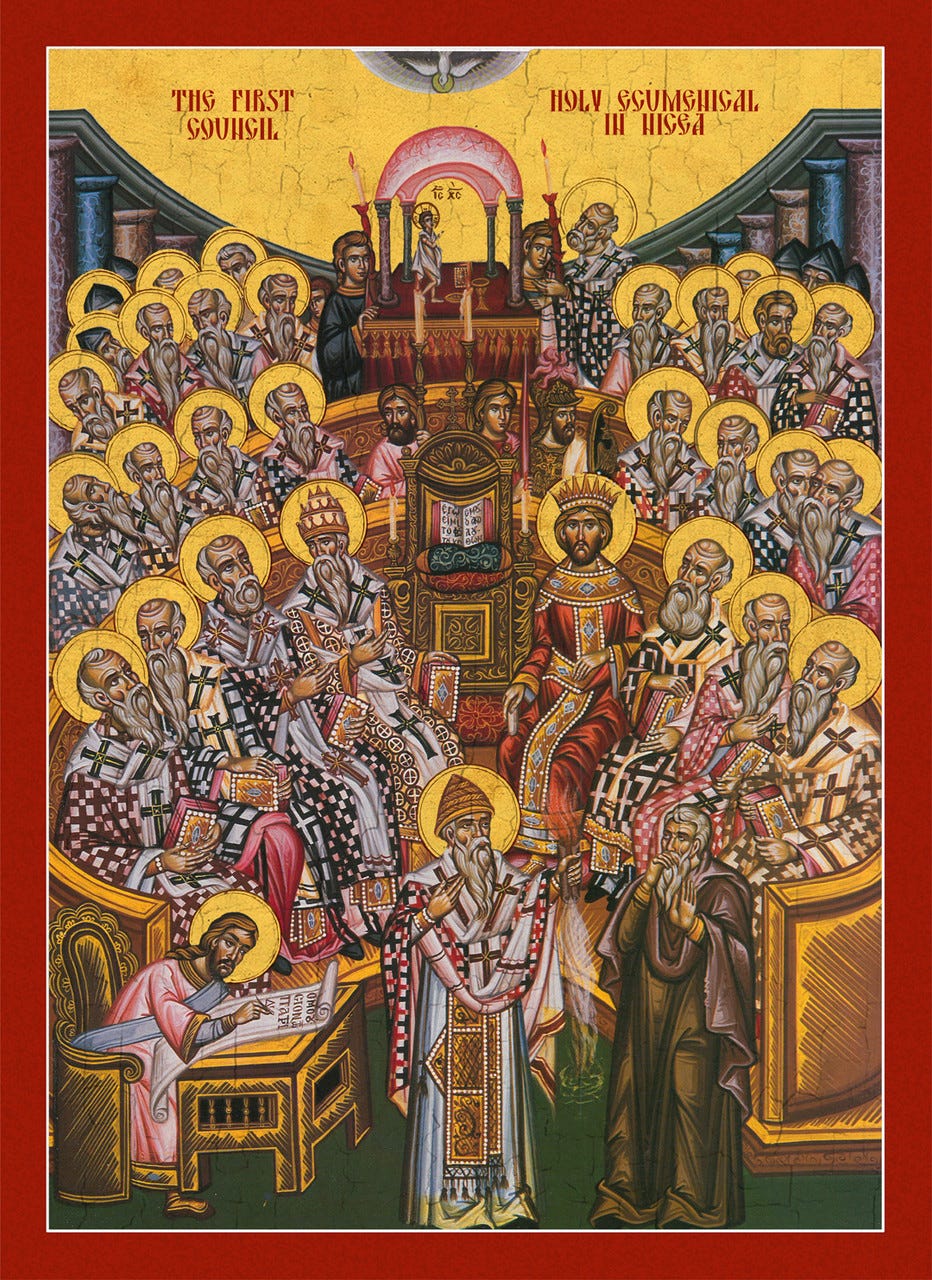

The historic church affirmed belief in the resurrection of the dead and the life of the word to come. Affirmation of the Nicene Creed is the minimum theological requirement to be considered orthodox (note the small “o”) within the historic church. This is why we recognize all who affirm the Nicene Creed as Christian, and we reject non-Trinitarian baptism. To borrow the idea of a Generous Orthodoxy from Brain McClaren (but probably not quite in the way that he meant it), the Creed as the critical statement of the faith, generously construed, includes not only the Catholic Churches, Orthodox Churches, some Protestants, it also includes the Church of the East and the Oriental Orthodox. Inclusive as that is, it excludes as well. It excludes non-Trinitarians. It excludes non-Christians, including those who might believe in Yahweh but who also worship demons (pagans). And while the creed does not mention witchcraft, the scriptural texts and Holy Tradition are abundantly clear upon this topic.

So, this is the why: while I am not a fan of gatekeeping, The Episcopal Church and Anglican Communion must adhere to the ancient standards of membership. Holy Baptism, which is administered after assent to the Nicene Creed by the catechumen to the priest or bishop, in front of the Congregation and Godparents, who all affirm to look after the spiritual welfare and formation of the catechumen become Christian.

The creed itself, then, is the foundation of Christian theology. It is the gateway to the first sacrament, which then opens up the door to the other Holy Mysteries of the Faith.

As the Creed is the standard of faith, my position then is one called Inclusive Orthodoxy. I welcome all as fellow Christians who have been validly baptized. That includes all brothers and sisters in Christ, and even those who don’t identify as brothers and sisters. While questions of Gender and Sexuality are important topics of theological anthropology, hamartiology, and soteriology that must be discussed and struggled with even in 2024, they are not proclaimed within the creed. Therefore, I welcome my those who are unlike me, because I am convinced that Christ welcomes them also. I do not have to understand the point of view of others in order to respect the creed as the Standard of the Faith. The gender and sexuality of another is between themselves, God, and, I would argue, their spiritual mother or father in the faith. (While this last qualification flies in the face of modern notions of individual agency, I believe that the ancient practice of submitting to a spiritual director is one that ought to be restored. That said, a spiritual father or mother must be carefully selected).

Now that I have defined and explained the why and its implications, lets get to the what/how:

I take as method the traditional methods of the Ancient Church: Holy Scripture and Holy Tradition, with two important additions: Reason and Experience. This merges the ancient Catholic/Orthodox/Church of the East understanding of the fount of theology, with the third plank from William Hooker, reaffirmed at in Chicago-Lambeth, as Reason. Some Episcopalians include a fourth, of experience, added by John Wesley, an Anglican Priest and co-founder of the Methodist Movement.

So, our formulation of theology, I suggest, should include Holy Scripture, Reason, Experience, and Holy Tradition. And Holy Tradition is what I wish to focus on for the rest of this post.

I believe than a worthwhile theological method is attempting to reconstruct the theology of the Early Church. One of the affinities that I found between my former religious affiliation and formation (Restorationism), and Anglo-Catholicism in the Episcopal Church is an emphasis on the Early Church. Anglicanism has always drawn deeply from the Fathers and Doctors of the Church, and should continue to do so. However, I also encourage Anglo-Catholics to draw deeply from a more diverse set of Church Fathers. I believe we should also draw much more deeply from the traditions of the Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, and Church of the East.

Why why of this is two-fold: first, I recognize members of these churches, including Catholics both Eastern and Western, as fellow Apostolic Christians (even though we are out of communion), and because through the use of comparative, historical theology, we can reconstruct a common theological core of belief for the Early Church. And for those who value their theological freedom, it provides a endless well of historically understood ways of understanding the Christian faith in ways that are orthodox. In shortness, the method opens Anglicans to the fullness of the faith, but also restricts definitive theology in terms of beliefs universally held by all Christians of the ancient church.

The implications of such an approach are vast. For some Episcopalians, the most questionable thing about Anglo-Catholics is our propensity to seek the prayers of the Saints, or to say prayers for the dead. Or, of course, veneration of the Blessed Virgin Mary. However, reexamining the early church through the understanding of the ancient church as a whole requires that we ask deeper questions, such as:

What about theosis?

What truly is worship?

What is the true point of worship?

What is the authority of the church and its Bishops?

How do we relate to other Apostolic Christians who vehemently disagree with Anglo-Catholic Theology?

So, after having laid out why I want to suggest a more solidified Anglo-Catholic Theology for our churches, as well as a very basic theological method that expands our theological source material known as Holy Tradition, and then suggestion a few things we ought to think about in light of these additional sources of tradition, I want to suggest one more thing: A different way to think about the possibilities of Anglo-Catholic identity.

I will admit that the following idea may appear somewhat convoluted and contrived. I’m still thinking through the implications and details. But I think such an idea will hold water. I’ve talked to hard-core Anglo-Catholics, who are Roman Catholic in everything but allegiance to the Pope. They’d make excellent, traditional Old Catholics. I’ve also met plenty of Anglo-Catholics who are so in practice only, and hold to a much stricter broad church theology. I’ve also met Anglo-Catholics who call themselves “Anglo-Orthodox” or “Anglo-Catholic, Orthodox Sympathizers.” I myself fall into this category. While I’ve never seen anyone call themselves “Anglo-Catholic, Church of the East Sympathizers” (probably for a number of reasons), I do believe the Church of the East also has things to teach us about ancient Christianity and how its adherents understood it. One thing that Anglicanism and the Church of the East have in common theologically that the other churches do not is that of the Open Communion Table. Beyond that, however, there are countless points of agreement between the Church of the East and the other Apostolic Churches. And where those points all come to confluence, we can reliably come to a tentative agreement upon the bounds of Anglo-Catholic Doctrine.

However, because this method is more expansive, a way to think of it is this: The Bishop of Rome, and the Patriarch of the West, is also in full communion with Catholic Churches that used to be a part of the other communions. This includes parishes that were Eastern and Oriental Orthodox, Church of the East, and through the Ordinariate of the Chair of St. Peter, the Anglican Communion. So, while rejecting Roman dogmas that exceed our own, we might consider ourselves Anglo-Eastern Catholics. We are free to draw from these deep theological wells of the “Great Church” Era, and the wisdom and practices that it has to share in our formation, practice, and lives as Christians. While clunky (and I don’t expect anyone to call themselves that!) the term does suggest both a theological way forward and also a theological impossibility at the same time. Following a theological method may very well create a common set of theological understandings for a large group of people, but it probably will evetabally create multiple sets of those common theological understandings. However, that is where the commitment of unity in diversity of the Anglican Communion will serve this method well. We have few dogmas (but we have them!). We have much freedom to read, interpret, and practice theology beyond that. But we also have a map to do so, even if that map requires the use of scholarly amplifications of that map to fully form the nous (mind) of the church.

What do you think of this as a very simple framework for a theological method for Anglo-Catholicism? What is missing? Is anything shortsighted? What else needs to be thought out?

Note: I understand some Anglo-Catholics object to the inclusive part of Inclusive Orthodoxy. I’m not here to debate that today.